By Guest Columnist Mary Jane Boutwell

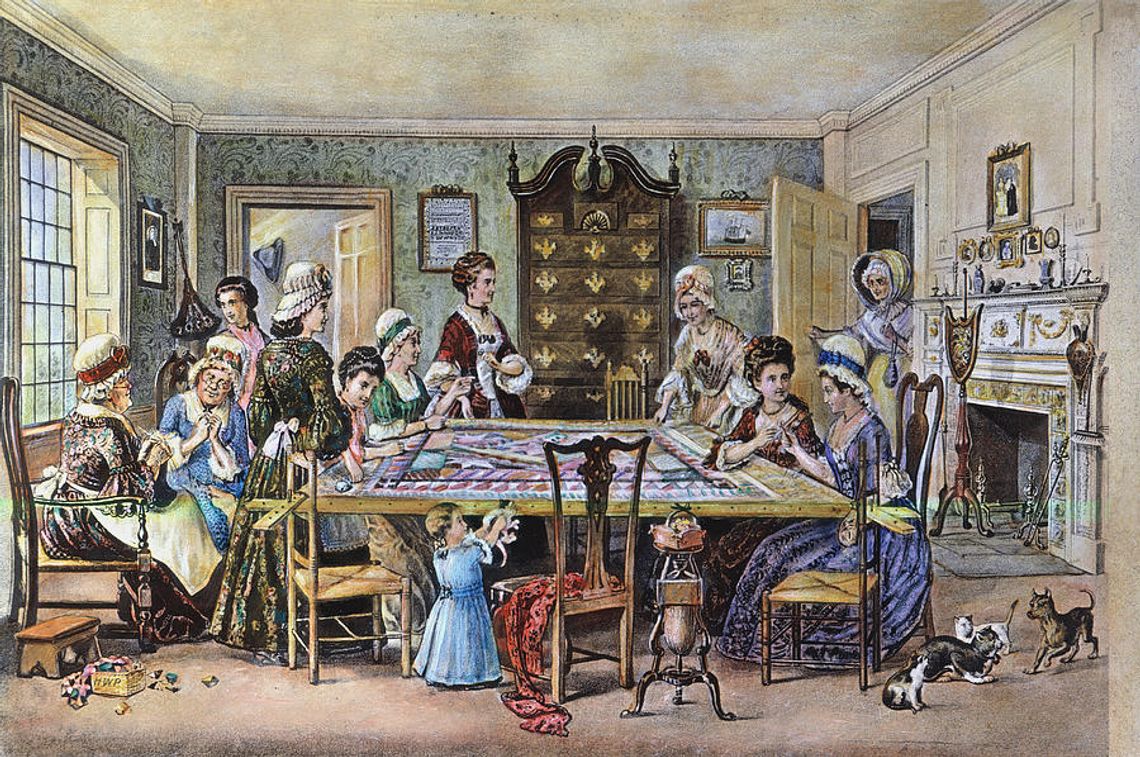

Quilts and quilting have been on my mind the last few weeks. One thing that started a lot of looking back, reading, and telephone calls has been quilting bees. Over the years a lot of quilt-related literature has presented the Bees as a common ongoing event. My memories of women getting together center around the monthly home demonstration that was both social and educational. Also, meeting at the church for pot-luck dinners on the ground[no air conditioning] or the pot-luck for the last night of the week-long revival. In my family, Christmas Day get together or when a family member from out of town states was at our house. Food, talk, and occasionally someone left early, but no quilting.

Most of the quilt conversations concerned either hand or machine quilting using fabric on hand, scraps, old cloth or sacks (feed, sugar, flour, rice, salt, fertilizer or other).I have a quilt Maw, my mama, cut the pieces from feed and fertilizer sacks Her mama, Mama Nervy, pieced and then it was quilted on the home sewing machine. No quilting bee.

In talking with quilters and descendants of quilters throughout the state, the consensus has been that mamas and grannies made the tops and when in the quilt from the actual quilting was done when there were a few minutes of down time before going to bed a few minutes after dinner was done before heading back out to the field or whatever job was waiting. The closest to a quilting bee was when a neighbor stopped by while quilting was being done, sometimes folks would stop by to learn how to quilt.

One lady told me her mother bought the quilt batting and worked on it as above. But, her grandmother used homegrown cotton. The grandkids would visit, play under the quilt, and pick out the dark trash in the cotton. My mother had a drawer where she kept scraps. When it got full, she took them to the machine and made tops-no pattern, just scraps sewn together. I showed one of these quilts to my younger brother and pointed out scraps from several of my homemade clothes. He, James Leslie Showell, showed me scraps from his pajamas.

These machine made quilts for cover used cotton samples for batting. The samples were packed in the same closet as the scraps. The samples were pulled apart, spread over the top, the backing placed on and to the machine it went. Using the cotton this way meant it should be closely quilted as the cotton shifted with use. The quilt frame was four long 1x2 boards with the quilt attached on all four sides to strips of fabric tacked to the wood. As it was quilted it was up on the opposing strips and kept tight with clamps or pegs in the holes in the wood. The one in my parents’ bedroom hung from four fence staples that were still there after raising our children in the same house and finally bulldozing it down.

Years ago, Bernice Jefferson told the story of her first quilt. As I remember it, the pattern was the Double Wedding Ring- alot of small pieces. Bernice was in high school. Her mother gave her scraps as did neighbors and the postmistress. She saved her money from different jobs and went to buy the backing, showing exactly what she wanted. As it happens, she came home with something different.

The next need was the batting. A neighbor farmer told her she could scrap his cotton field. When she got what she could, she took it to the cotton gin and asked a family friend who worked there if he could ger it ginned for her. He said “yes.” When Bernice went to pick up the ginned cotton, the gentleman told her he added some to make sure there was enough. Bernice said the hardest part of the quilt was after spreading the cotton, she had to whip it. This leveled the cotton and helped it interlock the fibers so they did not shift as badly. The quilt was used only one time. It survived long-distance moves and housefires.

When Bernice told the story, she was sad that none of her family wanted to quilt. It was suggested that she write the story and take it to the Smith Robertson Museum. It was felt that the museum would be pleased to add it to their collection. After the story was written and the daughter knew the story, she gladly took the quilt.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mary Jane Boutwell is a passionate historian and is thrilled to share stories about way back when.

.png)

Comment

Comments